Battle of Mantinea

Battle of Mantinea (418 BC)

GO DIRECTLY TO:

Battle of Mantinea (418 BC)

Battle of Mantinea (362 BC)

THE PEACE OF NICIAS

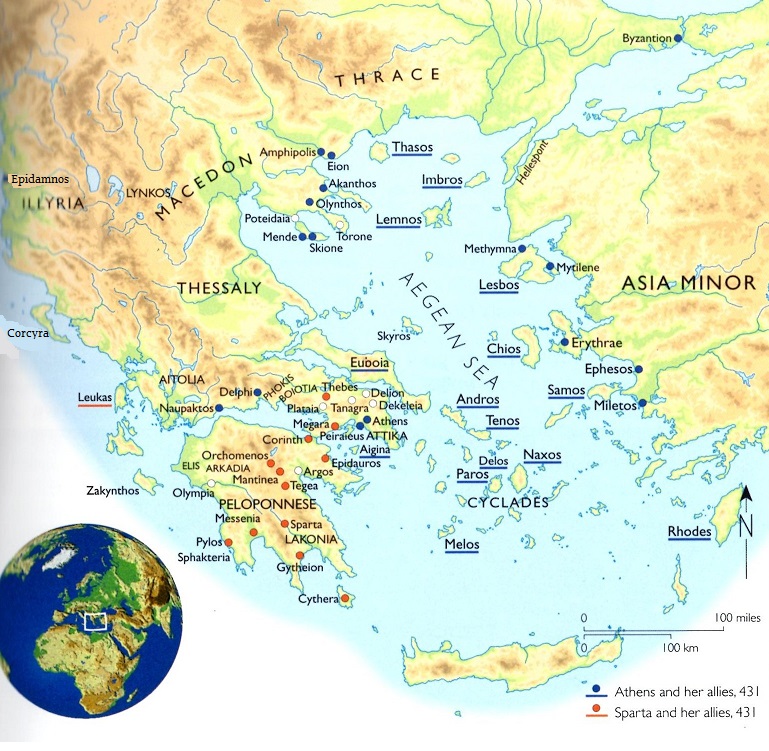

Signed in 421, the Peace of Nicias ended the first half of the Peloponnesian War. It came none too soon for the belligerents. Both sides were exhausted, and the leaders of the "war-faction" in each state, Brasidas and Cleon the Tanner, had fallen at Amphipolis.

For the Spartans, the war had seen the legend of her soldier's invincibility in battle shaken; with Spartans surrendering (!) at Sphacteria Island, and Athens putting the 292 prisoners on display. Brasidas had partially retrieved Sparta's reputation and fortunes with his brilliantly-conceived northern campaign (see Part 5). But this hero's death at Amphipolis had taken the heart out of the city and deprived it of its greatest commander.

Athens had suffered as well in this decade of war against the Spartans and their allies. In 424, an Athenian attempt to knock Thebes out of the war ended in disastrous defeat at the Battle of Delium. This, combined with the effect Brasidas' northern campaign and the loss of Amphipolis had on their position in the strategically vital northern Aegean, made peace as desirable for them as well. With the death of the bellicose demagogue Cleon the Tanner (also killed at Amphipolis) the way was cleared politically in Athens for a treaty to be signed.

Negotiated primarily by the Spartan king Pleistoanax and the Athenian statesman Nicias, under its terms both parties were prohibited from taking up arms against the other (or the other's allies). Both would return nearly everything conquered during the war; though Athens would retain possession of the captured Megaran port of Nisaea; and Thebes would keep captured Plataea. Sparta offered to return Amphipolis, with the proviso that the inhabitants could leave the city with their possessions if they didn't wish to be under Athenian rule. Additionally, the Athenians were prohibited from making war upon the Greek cities of the Chalcidice, freed by Brasidas, or forcing these to become "allies" of their empire; provided these cities of the former Delian League (an alliance of Aegean cities formed to help in the old war against Persia; which had morphed, under Pericles, into an Athenian Empire) paid the League tribute established in the time of Aristides. Of course, Amphipolis was an exception to this clause, being returned to Athens; with-or-without the inhabitants!

Perhaps most importantly for Sparta, Athens agreed to release the Spartans taken at Sphacteria. These had languished in humiliating captivity since 424, and included 120 true Spartiates.

Astonishing to Sparta's anti-Athenian allies (particularly Corinth and Thebes), the treaty returned Sparta and Athens to the status of allies they had enjoyed during the Persian War. Each now pledged to come to the other's aid if attacked.

Seventeen representatives from each side swore an oath to uphold the treaty, which was meant to last for fifty years. Among the Spartan representatives was Tellis, father of the fallen hero Brasidas.

BATTLE OF MANTINEA (418 BC)

The terms of the treaty pleased few of Sparta's allies, who had gone to war with the intent of humbling Athens and breaking her power. The Athenian Empire was still strong, and left in possession of territories wanted by some of these enemies. Disillusioned with Sparta's ineffectual conduct of the war and willingness to make peace (and alliance!) without victory, many of these now turned away from Spartan leadership.

Corinth, Megara, Thebes, and Elis refused to accept the terms of the peace.

Sphacteria had shown that Sparta was not invincible. This emboldened these disaffected Peloponnesian states to align against her. Many of these were democratic and unsympathetic with Sparta's traditional oligarchic stance. Others saw a chance, after a century of Spartan dominance, to assert their independence.

At the instigation of Corinth, these disaffected Spartan allied cities turned to Argos, Sparta's traditional rival in the Peloponnese for leadership.

The Argives had always hated Sparta, and suffered crushing defeat against them during the reign of Cleomenes I, before the Persian War. Since then, Argos had remained quite, nursing her grudges and biding her time. She had remained neutral during the war, and thus her economy and strength were still sound.

The Argives now formed a secret anti-Spartan alliance of their own. Along with Corinth, the democratic states of Mantinea and Elis joined their fellow democratic Argos. Too weak to openly oppose both Sparta and Athens, this alliance remained secret for the time being.

Perhaps these anti-Spartan allies knew that the Peace of Nicias would never last. That once each had licked their wounds and recovered their strength, these two diametrically opposed cities would once again be at odds.

Athens was the first to violate the terms of the peace. Refusing to withdraw from its fortified base at Pylos, which they had garrisoned with liberated and armed helots; the Athenians demanded that Sparta bring her disaffected allies to heal, forcing them to accept peace with Athens. This could mean making war on its own allies, affectively destroying the Spartan Alliance. This Sparta would not do. To make matters worse from the Athenian perspective, the ephors renewed the alliance with Thebes; despite that city still being (technically) at war with Athens.

In Athens, the elder statesman Nicias found himself defending the peace that bore his name; as the volatile Athenians turned against it. Their expectations of a fully-restored Athenian Empire were unfulfilled. In the north, the people of Amphipolis refused to hand over their city as the Peace of Nicias outlined; and the other cities of the Chalcidice, freed by Brasidas, were still in arms against Athens. Under the terms of the peace, the Theban refusal to make peace should have evoked a Spartan attack; instead, Sparta renewed her Theban alliance. Anti-Spartan sentiment was again on the rise.

Nicias and "peace party" found themselves up against the machinations of a rising young star in the city's politics: Alcibiades. A relative and former ward of the late Pericles, Alcibiades had wealth, wit, good looks and boundless ambition. He was also completely lacking in scruples, and was willing to do anything to advance his own fortunes.

Wrapping himself in the mantle of Pericles, Alcibiades became the leader of the aggressive imperialist and anti-Spartan faction in the city. In this capacity, Alcibiades now secretly entered into negotiations with Argos and her allies; all the while sabotaging every effort to repair relations between Sparta and his city.

In 420, Athens formed a defensive alliance with Argos, Mantinea, and Elis. Though Corinth had instigated the anti-Spartan coalition, that city now hedged its bets and remained aloof. That same year the Eleans, on whose territory was Olympia, prevented the Spartans from taking part in the Olympic Games!

War broke out in 418 between Sparta and the Argive allies. In Athens, Alciabiades was not elected to the Board of Generals (the Athenian version of a General Staff); and as such had no official role. However, he was in Argos agitating the allies against Sparta.

By choosing to join the Peloponnesian democrats against its ally, Sparta, Athens decided to all but tear-up the Peace of Nicias. But the Athenians were unwilling to openly declare hostilities again, so soon after the ending the war. Therefore, they held back from committing their Army to this anti-Spartan alliance; only sending that token force of "volunteers": enough to enrage Sparta, but not enough to ensure its defeat. Had the full Athenian army marched beside the Argives and other allies, the decision in the coming battle might have gone very differently.

The Argive army gathered at Mantinea, an excellent site for a hoplite battle; one that would see three such clashes over the next two centuries of Greek history. This would be the first such on this plain. The Argive and allied army included a token force (1,000 hoplites and 300 cavalry) of Athenian "volunteers"; this despite the fact that Athens and Sparta were not only at peace, but technically allied. With her leadership in the Peloponnese on the verge of collapse, the Spartan army marched north under King Agis II to meet the challenge.

Agis arrived with a Spartan army estimated at 18,000 strong[2]; the core of which was some 3,600 Spartiates (the "Equals"). Seldom did the full muster of Spartiates ever take the field together. Normal practice was for the Spartans to send no more than a few hundred of their excellent hoplites as a leavening, to bolster the fighting power and provide leadership for an expeditionary force of their allies. It is a sign of how dire were the circumstances that the full Spartan muster took the field for this campaign.

The Spartans found the Argive forces, slightly smaller in number, holding a very strong position on high ground. Advancing against them, the opposing phalanxes were within "a stone's throw or javelin's cast" of each other when a veteran Spartan called out to the King, warning him that he was making a mistake in engaging the enemy in such a strong position.[3] Seeing his error, Agis halted the advance, and the Spartans pulled back unmolested.

Now the problem was to draw the Argives down from their position, to the plain below. To achieve this goal, the Spartans began devastating the territory around Mantinea; even diverting a local river in order to flood the Mantinean plain! With their fields in danger of destruction, the Mantineans convinced the rest to come down and face the Spartans on the flat ground. Marching onto the plain, the Argives and their allies deployed for battle.

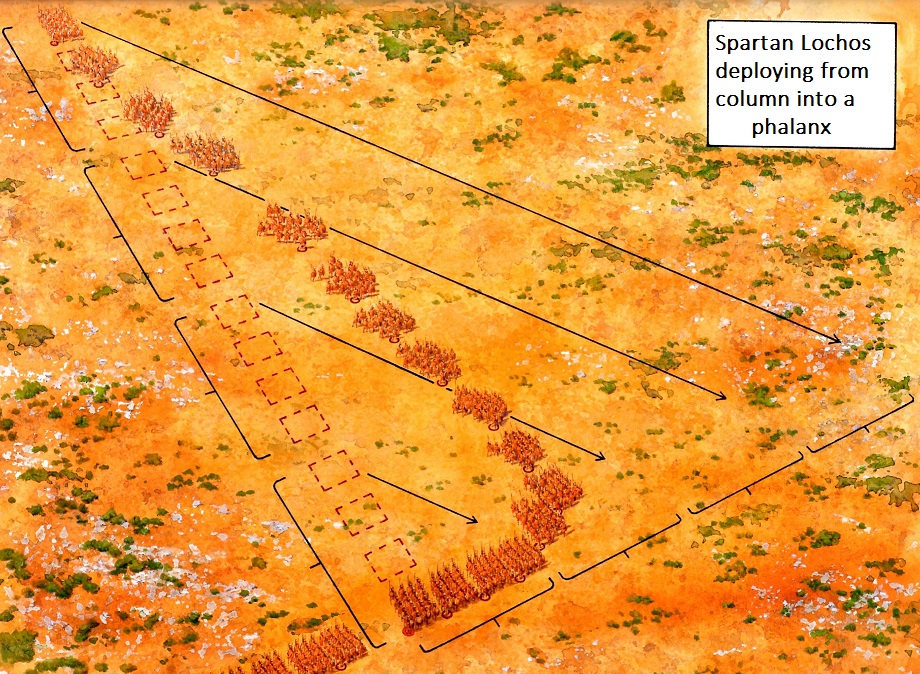

Perhaps expecting to catch the allies unready, the Spartan forces, coming out of a wood, were (according to Thucydides, a contemporary) astonished to find the enemy drawn up in line; standing to arms on the plain and prepared for battle. Thucydides states that never were the Spartans more "shocked" than they were at this sight[4]. Despite this, the perfectly drilled Spartan hoplites quickly and efficiently deployed from column into line of battle.

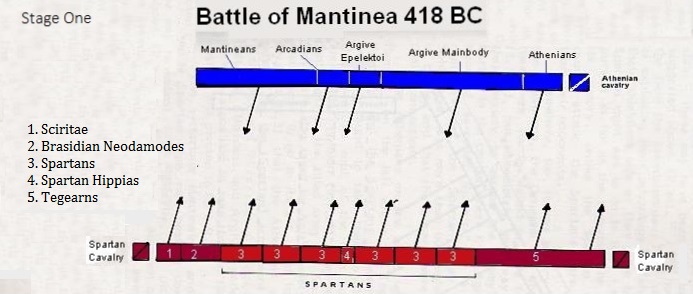

The Spartan regiments (lochoi) took the center of the line; with the Hippias (the Spartan Royal Guard), in the center of these around King Agis. The Tegean and Arcadian allies were placed to their right. On the Spartan's left were the Neodamodes and other veterans of Brasidas' northern campaign (the "Brasidians"); and beyond these, holding the extreme left end of the line, as was customary, were the 600 Skiritae, elite light troops from the northern mountains of Laconia. In all, there were some 12,000 Peloponnesian hoplites, about 5,000 light-armed infantry, and about 500 cavalry on either flank.[5]

Across the field the allied army numbered approximately 11-12,000 hoplites, nearly as many as the Spartans. Opposite the Skiritae were 2,000 skilled Mantinean hoplites on the allied right. Beside these were an equal number of Arcadians. In the center of the allied line were the Argives. The right-most unit of these were 1,000 elite Argive "Epelektoi" (Picked) hoplites. The remaining Argive hoplites (5,000?) along with the Eleans and the contingents of other, smaller cities also occupied the center, staring across the field at the red-cloaked Spartans. The Argive left was held by the 1,000 Athenian hoplites and their small contingent of cavalry.

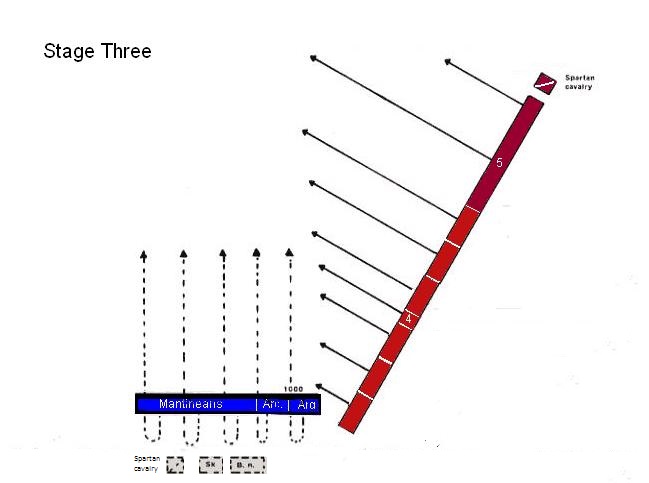

Agis noted that the enemy line extended beyond his left flank. Attempting to correct this, he ordered the Skiritae and the "Brasidans" to extend to their left, while ordering two units from his right to march behind the line and take station in the gap this move created in the Spartan line. Both commanders refused the order, the enemy being too close to contact (both were subsequently "cashiered" and exiled for disobeying orders). Because of this, a dangerous gap developed in the Spartan line.

The allied line advanced rapidly, shouting encouragements to each other and singing their battle paeans. Here, as at Pylos, they would teach the Spartans another lesson!

The Spartans, by contrast, tramped forward in eerie silence, to the trilling of pipes.

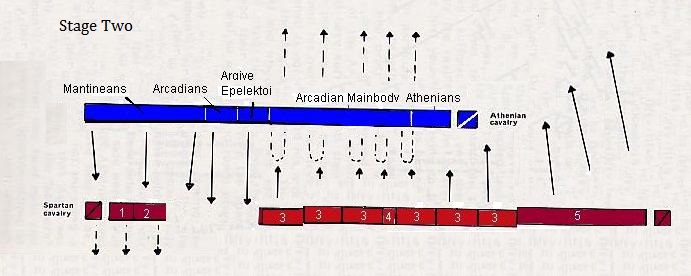

The Mantineans, Arcadians and the Argive "Epelektoi", some of the best hoplite warriors in the world, smashed into the light-armed Skiritai and the Brasidians. Isolated from the Spartan center, these bore the full brunt of the enemy's main effort. Unable to withstand this attack, they fell back toward the Spartan baggage camp.

The situation played out very differently in the center and on the Argive left. Here the scarlet-clad Spartans advanced with lowered spears and locked shields. The sight was one that instilled terror into the hearts of their opponents. Despite their loss of prestige following Sphacteria, the Spartans were still the most feared infantry in the world!

Without waiting to meet their onset, the Argives and their allies on the left broke ranks and ran; all their brash talk of a second Pylos forgotten! Thucydides states that they trampled each other in their haste to escape the Spartan spears. Not all were so lucky: the Athenian commander, Laches, was stabbed in the back while attempting to flee.

Agis, keeping his troops in hand, now wheeled his line hard to the left, cutting down fleeing Argives as they did. A lifetime of military drill and practice now showed its worth; as with machine-like precision the Spartan center and right turned 90 degrees to face the hitherto victorious Argive right wing.

There the Mantineans, Arcadians and the Argive elites were fighting over the Spartan baggage, where they killed many of the older men left as guards. No doubt celebrating what seemed a striking victory, they had no idea their doom was wheeling toward them.

The Spartan line bore down upon their right flank, the shieldless side of any hoplite formation. The effect was devastating, the Spartan phalanx grinding into the flank of the allies and cutting them to bloody pieces. The Spartans showed no mercy, except for the Argive "Epelektoi"; who were allowed, for political reasons, to escape the battlefield. Sons of the aristocracy, these would return home to Argos to oppose the anti-Spartan democratic government.

Mantinea was a complete triumph for the Spartans. In one day's fighting, in the largest hoplite battle of the Peloponnesian War, they had regained their lost reputation as Greece's invincible warriors. Never again, in the course of the conflict, would any Greek army challenge them on land.

Battle of Mantinea (362 BC)

The Second Battle of Mantinea was fought on July 4, 362 BC between the Thebans, led by Epaminondas and supported by the Arcadians and the Boeotian league against the Spartans, led by King Agesilaus II and supported by the Eleans, Athenians, and Mantineans. The battle was to determine which of the two alliances would have hegemony over Greece. However, the death of Epaminondas and his intended successors coupled with the impact on the Spartans of yet another defeat weakened both alliances, and paved the way for Macedonian conquest led by Philip II of Macedon.

Background

After the Battle of Leuctra in 371 BC had shattered the foundations of Spartan hegemony, Thebes' chief politician and general Epaminondas attempted to build a new hegemony centered on his city. Consequently, the Thebans had marched south, into the area traditionally dominated by the Spartans, and set up the Arcadian League, a federation of city-states of the central Peloponnesian plateau, to contain Spartan influence in the Peloponnese and thereby maintain overall Theban control. In years prior to the Battle of Mantinea, the Spartans had joined with the Eleans (a minor Peloponnesian people with a territorial grudge against the Arcadians) in an effort to undermine the League.

When the Arcadians miscalculated and seized the Pan-Hellenic sanctuary of Zeus at Olympia in Elis, one of the Arcadian city-states, Mantinea, detached itself from the League. The Spartans and Eleans joined the Mantineans in a military attack on the Arcadian League. Athens decided to support the Spartans, as she resented the growing Theban power. The Athenians also recalled that at the end of Peloponnesian War, the Thebans had demanded that Athens be destroyed and its inhabitants enslaved; the Spartans had resisted these demands. An Athenian army was sent by sea to join the Spartan-led forces, in order to avoid being intercepted on land by Theban forces. Epaminondas then led a Theban army into the Peloponnese to restore order and re-establish Theban/Arcadian hegemony there.

Battle

The two armies met near Mantinea in 362 BC. The Spartans, Athenians, Eleans and Mantineans were led by the Spartan king, Agesilaus II, who was assisted by Podares of Mantinea and Cephisodorus of Marathon, the commander of the Athenian cavalry. The Theban army also included contingents from city-states of the pro-Theban Boeotian League. Epaminondas' Thebans were assisted by the Arcadians loyal to the League, principally those from the city-states of Megalopolis (founded by the Thebans when they were last in the Peloponnese, as the Arcadian federal capital) and Tegea (the traditional leading city-state of the Arcadians).

Though both generals were highly competent, Epaminondas prevailed at Mantinea. Using a modified version of the tactics he had successfully pioneered at Leuctra, he organised the Boeotian troops on the left wing of his army into an unusually deep column of hoplites. This formation of troops, in conjunction with the echelon, sought to establish local superiority of numbers while delaying the battle on the weaker center and right side. As Greek battles were pushing-matches, it allowed the large, dense section of the line to force its way through the thinner classical phalanx. Epaminondas personally led this column from the front line. Xenophon (Hellenika 7.5.23) described the left wing of that Theban army as "like a trireme, with the spur of the prow out in front."

The Theban cavalry and light infantry drove off the enemy cavalry. The Theban hoplites marched in a column across the face of the enemy line, then performed a smart wheel and crashed into the enemy right, where the Mantineans were positioned. The Mantinean leader Podares offered heroic resistance, but when he was killed the Mantinean hoplites fled the field. However, in the thick of the fighting, Epaminondas was mortally wounded by a man variously identified as Anticrates, Machaerion, or Gryllus, son of Xenophon. The Theban leaders Iolaidas and Daiphantus, whom he intended to succeed him, were also killed.

Aftermath

On his deathbed, Epaminondas, upon hearing of the deaths of his fellow leaders, instructed the Thebans to make peace, despite having won the battle. Without his leadership, Theban hopes for hegemony faded. The Spartans, however, having been again defeated in battle, were unable to replace their losses. The ultimate result of the battle was to pave the way for the Macedonian rise as the leading force who subjugated the rest of Greece, by ensuring the weakness of both the Thebans and the Spartans.

Sources

[1] "Scout" by BARRY C. JACOBSEN

[2] "Wikipedia"